The Bloom filter data structure tracks set-membership in a fast and space-efficient way. I first heard about Bloom filters when I saw them used in speeding up database search. Then, I heard about Microsoft using a stack of Bloom filters to speed up the Bing search engine’s keyword search.

In this project, I implemented a Bloom filter and a bit-sliced document signature in C. I also wrote unit tests and a collection of fun demos to show how Bloom filters and bit-sliced signatures can be used. This report gives an overview of the project, demos and results, and notable code design decisions.

Table of Contents

1 PROJECT GOALS AND RESULTS

I wanted to learn about Bloom filters because I have heard about their interesting real-world applications. I particularly wanted to implement a extension of Bloom filters called bit-sliced signatures that I heard of in the talk “BitFunnel: Revisiting Signatures for Search” talk by Micheal Hopcroft, creator of BitFunnel. This was an interesting Software Systems project because many Bloom filter implementations are done in C/C++ in order to have full control and optimization of low-level bit-wise operations

Thus, in terms of experience goals, I wanted to gain experience designing and using bit-wise operations, structs, function pointers, file pointers, enums, linked lists, Makefiles, writing modular code, and other programming concepts I learned about in class. (See section: 4.1 Note on Code Design for more information about my specific coding design decisions).

My highest bound was implementing some of the optimizations used by Bing search engine’s BitFunnel algorithm. However, the BitFunnel algorithm reached its best performance improvements by simply sharding its gigantic corpus intelligently (i.e. binning documents by number of unique terms) so that they could store shorter document signatures in less space but still have precision for larger documents. This design decision makes sense for a production information retrieval system that was already sharding its corpus, but makes less sense for me. Therefore, for this project I pivoted to an actionable upper bound: a set of demos that demonstrate various aspects of Bloom filters and bit-sliced signatures and provide me with an intuition of how to use them.

Overall, I met the higher bound for this project. I successfully implemented a Bloom filter and bit-sliced signatures, and made some really pretty and fun demos.

Demo 1: Bloom filter spellcheck, demonstrate actions of create, add, save, query from stdin, and ability to load and add to previously saved Bloom filter

make demo_bf_spellcheck

make demo_bf_spellcheck_w_Gati

Demo 2: Bloom filter to spellcheck this project’s README file (super useful!)

make demo_bf_spellcheck_readme

Demo 3: bit-sliced signature based document matching, retrieve list of xkcd comics that contain the keywords in a user query

make demo_bss_xkcd_query

See the full MakeFile for more demos and list of all the executable programs. All files and programs are properly documented in the header files, and for any executable, running <program_name> -h will reveal argument details for running the program.

See test and demo output results in the results folder.

2 BLOOM FILTERS

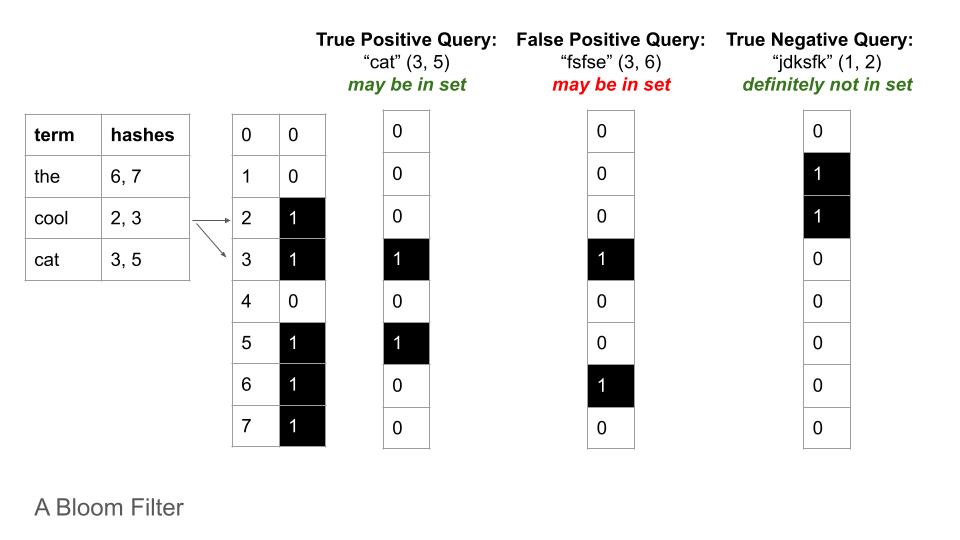

The Bloom filter is a probabilistic, space-efficient data structure that can tell you whether an object is in a collection with the possibility of a false positive. It does not store the terms directly, it just stores indicators (a.k.a. hashes, probes) of each term’s presence.

Bloom Filter

False positive matches are possible, but false negatives are not: so given a query it can either return “possibly in set” or “definitely not in set”. This false positive rate can be controlled by increasing number of bits and increasing number of hash functions (See section: 4.2 Note on Controlling False Positives).

The probabilistic feature allows Bloom filters to do membership validation in very little time and very little space. So these Bloom filter lookup tables can even be stored in a browser cache without taking up a significant amount of space. In the real world, Bloom filters are used to quickly tell you if a username is taken, or to quickly check if a website is known to be malicious. They have also been used as spell-checkers and filters for censoring words. The start-up I was interning for last summer implemented a Bloom filter to speed up their database querying times by avoiding checking the database for almost all items which won’t be found in it anyway, thus saving a lot of time and effort.

Real World Use-Cases:

Bitly uses a special type of Bloom filter to keep track of an ever-changing list of malicious website that they should not create links for.

Bloom filters have also been used for tracing networks:

Other interesting use-cases to check out:

- Some Motley Bloom Tricks

- Look, Ma, No Passwords: How & Why Blackfish uses Bloom Filters

- Fast candidate generation for real-time tweet search with bloom filter chains

I implement two demos to show the functionality of Bloom filters.

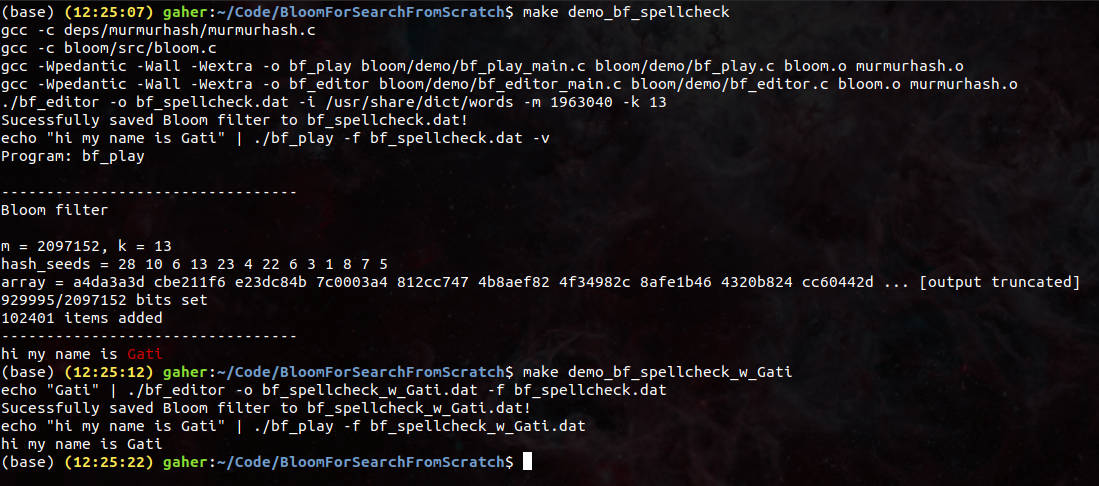

2.1 Demo 1: Bloom filter to spellcheck a query

My first demo creates a Bloom filter to check for properly spelled words. It uses a list of words from /usr/share/dict/words. For preprocessing, it splits terms by !\"#$%%&()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\\]^_{}|~.

It creates and saves the Bloom filter, and then loads and uses that Bloom filter to evaluate a query from stdin. In the first query it highlights my name (“Gati”) as spelled wrong, as it was not included in the original list.

Since I want my spellchecker to recognize my name, I use my Bloom filter editor program to load, edit and save the Bloom filter so that it recognize my name (“Gati”) as a properly spelled word. Then I load and use the new Bloom filter to evaluate the query again. This time, it recognizes my name as a correctly spelled word.

Demo 1: Bloom filter spellcheck

An important property of Bloom filters is that items can be added to it, but items cannot be removed, as deleting the set bits of a query may impact the set bits of other items.

The spellchecker demo adds 102401 terms, hashes each term with 13 hash functions, and stores everything in a bit signature of 2097152 bits (262KB). Using standard probability functions (explained on GeeksForGeeks, also this calculator), the saved Bloom filter I use for spellchecking has a 0.000054525 probability (1 in 18340 chance) of a false positive.

Furthermore, the resulting Bloom filter is ~262KB, which is 1/4th of the size of the original /usr/share/dict/words word list (972.4KB).

2.2 Demo 2: Bloom filter to spellcheck a file

My Bloom filter spellchecker can also be used to spellcheck files. I have a demo that uses my Bloom filter to spellcheck my README:

Demo 2: Bloom filter spellcheck README

In the screenshot you can see words flagged as incorrect highlighted in red. You can see that, in addition to flagging non-English words like “https” and “murmurhash”, it also flags words with atypical casing. For example, it believes that “It” is incorrect, as only “it” exists in its vocabulary.

This a super helpful tool for spellchecking my README.md and .txt files that do not have a built-in spellchecker! I can quickly read through it on my terminal and change words that are obviously spelled wrong. Using a Bloom filter as the first pass spellchecker limits the words I have to check manually, which allows me to utilize my brain power more effectively.

3 BIT-SLICED DOCUMENT SIGNATURES

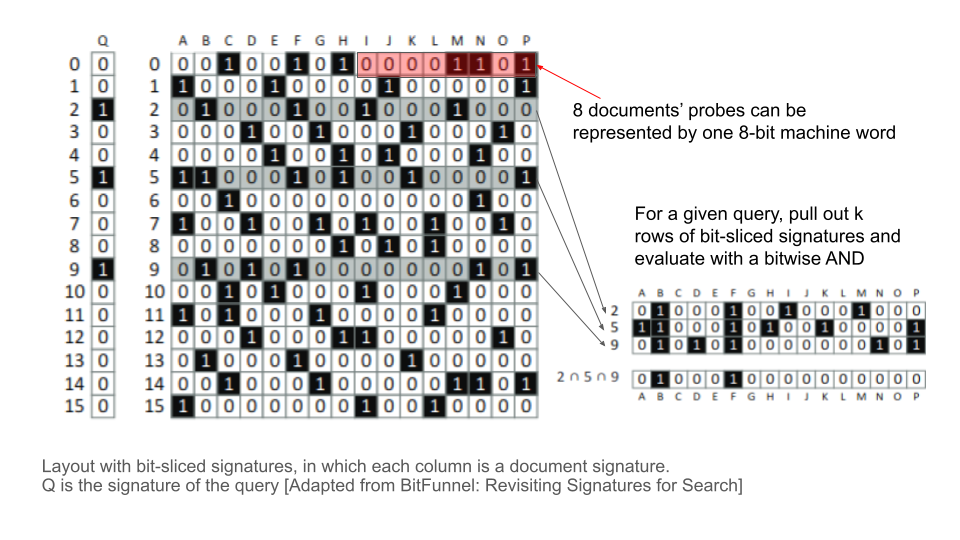

In addition to the Bloom filter, I also implemented a Bloom filter-based data structure called a bit-sliced signature. It that can be used to retrieve documents that contain all the words in a query.

A document can be represented by its document signature, which is just a Bloom filter containing all the terms in a document. If all the signatures have the same length and share a common hashing scheme, each document can be represented by a bit-sliced signature. In this approach, document signatures are stored in a big table, like a nested array of machine words (32-bit integers). Each row corresponds to one hash value. In the row, each of the 32 bits in an element correspond to 32 documents, and the bit is on or off depending on whether the document has the hash value.

bit-sliced signature

Given a query, the program builds a query signature by hashing each term in the query with the same bag of hash functions, and then checks if any of the document signatures have all of the query hashes. If all of the query hashes are not present in the document signature, there is no possibility of the document containing all of the terms in the query. However, since sets of terms can have the same hashes, there is a possibility of falsely saying all the query terms are in the document.

Real World Use-Cases:

All large-scale information retrieval systems use inverted indexes for efficiently performing data retrieval based on keyword search. However, adding a new document to an inverted index requires a costly global operation to update the posting list for each term in the document. To save time on this operation, invented indexes generally use batch updates. In order to support user queries on documents that are waiting on the batch update, e.g. people searching for real-time news, Bing uses a bit-sliced signature-based data structure called BitFunnel that can ingest new documents with a quick local update while also supporting rapid keyword search.

Bit-sliced signatures also frequently come up in the microbiology space, in particular when performing search on bacterial or viral data sets WGS data sets.:

3.1 Demo 3: Information retrieval on xkcd comics transcripts

So as a fun information retrieval demo, I decided to use my bit-sliced document signature to retrieve xkcd comics that match keywords. This is a fun tool to explore new xkcd comics for a topic.

In this demo, I add 40 documents (allocating two blocks of 64 bits), use signatures of length 512, and 3 hashes on each term. Each document comprises of the title, alt-text, and transcript of a given xkcd comic. This information is scraped from https://www.explainxkcd.com/ using a Python script with beautifulsoup.

As a demo query, I search for the term “outside”. This word actually appears in two documents: 30 and 14.

Here is an excerpt of the final results:

---------------------------------

Bit-Sliced Block Signature

m = 512, k = 3, num_blocks = 2

39/64 docs added

hash_seeds = 28 10 6

array =

197188 0

16908928 8

1694507008 0

17306112 0

17104896 0

-946130846 49

1092625410 0

1611989056 0

-105968822 187

165224480 8

... [output truncated]

colsums = 0 103 69 23 69 162 175 82 83 160 95 68 116 206 85 89

324 167 155 219 263 122 88 212 428 56 92 98 88 207 159 97

220 71 65 114 80 122 97 89 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

percent filled = 0=0.00% 1=0.20% 2=0.13% 3=0.04% 4=0.13% 5=0.32% 6=0.34% 7=0.16%

8=0.16% 9=0.31% 10=0.19% 11=0.13% 12=0.23% 13=0.40% 14=0.17% 15=0.17%

16=0.63% 17=0.33% 18=0.30% 19=0.43% 20=0.51% 21=0.24% 22=0.17% 23=0.41%

24=0.84% 25=0.11% 26=0.18% 27=0.19% 28=0.17% 29=0.40% 30=0.31% 31=0.19%

32=0.43% 33=0.14% 34=0.13% 35=0.22% 36=0.16% 37=0.24% 38=0.19% 39=0.17%

40=0.00% 41=0.00% 42=0.00% 43=0.00% 44=0.00% 45=0.00% 46=0.00% 47=0.00%

48=0.00% 49=0.00% 50=0.00% 51=0.00% 52=0.00% 53=0.00% 54=0.00% 55=0.00%

56=0.00% 57=0.00% 58=0.00% 59=0.00% 60=0.00% 61=0.00% 62=0.00% 63=0.00%

---------------------------------

Sucessfully saved bit-sliced signature to bss_xkcd.dat!

echo "outside" | ./bss_play -f bss_xkcd.dat -s "https://xkcd.com/%d"

4 Documents matching query:

https://xkcd.com/30

https://xkcd.com/24

https://xkcd.com/16

https://xkcd.com/14

My probabilistic data structure returns 4 matches: 30, 24, 16, 14. As expected there are the two true positives and no false negatives. However, documents 16 and 24 are false positives. Upon taking a closer look, the document signatures for documents 16 and 24 are 63% and 84% full respectively. That means, each bit has a higher than random chance possibility of being flipped, so the probability of the query hash being falsely present in the signature is pretty high.

To reduce the rate of false positives, I can increase the length of the bit signature so that it is less full. If I was using bit-sliced signatures in a production system, there are some interesting optimizations that reduce query speed, memory usage, and false positive rate (e.g. intelligent corpus sharding, weighted Bloom filters).

bit-sliced-signature representation in code

Here I talk though some key logic points from bitslicedsig/src/bitslicedsig.c

First of all, to really understand what was going on in bitsliced signatures, I first referred to the post Blocked Signatures in Java on Richard Startin’s Blog. It provided a good overview of the data structure and gave some abstract Java code to begin implementing it.

For my C implementation, I defined a struct to hold all the information that defined a bit-sliced signature.

typedef struct

{

u_int32_t m;

u_int32_t **bit_matrix;

u_int32_t k;

u_int32_t *hash_seeds;

u_int32_t num_blocks;

u_int32_t added_d;

} bitslicedsig_t;

The most efficient way to represent the represent the bit-sliced document signature’s bit matrix is as a nested array. This is the initialization function:

bitslicedsig_t *bitslicedsig_create(u_int32_t m, u_int32_t k, u_int32_t min_doc_capacity)

{

// due to integer division, this gets the minimum number of blocks to completely cover the given number of documents

bitslicedsig->num_blocks = (min_doc_capacity + WORD_SIZE - 1) / WORD_SIZE;

// I make the bit signature a power of 2 so I can use nice bit-wise operations instead of division in later steps

bitslicedsig->m = get_next_pow_2(m);

// initialize row pointers, where the number of rows corresponds to the length of the bit signature.

bitslicedsig->bit_matrix = (u_int32_t **)malloc(bitslicedsig->m * sizeof(u_int32_t *));

// for each row, initialize an array of 32-bit blocks, where each block corresponds to 32 documents

for (i = 0; i < bitslicedsig->m; i++)

bitslicedsig->bit_matrix[i] = calloc(bitslicedsig->num_blocks, sizeof(u_int32_t));

...

}

The main logic for both adding and querying essentially work the same way. I use a tokenizer and a while loop to turn an input into terms, and then I hash each term and set/check the corresponding bit.

I use modulus twice. The first fits the hash function into the proper range of my bit signature (while still keeping it random and independently distributed (see section 4.3 Note on Choice of Hash Function). The second finds the proper bit to set in the block.

...

// turn index into a column location inside of a block location, where WORD_POW = 5 (2^5 = 32) and WORD_SIZE = 32

u_int32_t blockIndex = index >> WORD_POW;

u_int32_t docWord = 1ULL << mod_pow_2(index, WORD_SIZE);

while (fgets(buffer, bufferLength, f))

{

rest = buffer;

while ((token = strtok_r(rest, " !\"#$%%&()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\\]^_`{|}~", &rest)))

{

if (token[strlen(token) - 1] == '\n')

token[strlen(token) - 1] = '\0';

/* hash each term with each hash function */

for (h = 0; h < bitslicedsig->k; h++)

{

// hash the token to generate a hash

hash = murmurhash(token, (u_int32_t)strlen(token), bitslicedsig->hash_seeds[h]);

// decide what row to set by taking hash % number of bits

hash = mod_pow_2(hash, bitslicedsig->m);

// set the bit in array by changing specific bit of specific word

bitslicedsig->bit_matrix[hash][blockIndex] |= docWord;

}

}

}

...

While performing the query logic, I attempt to find an intersection of all the query hashed rows. When intersecting a set of rows, the outer loop goes over the register-sized chunks in each row and the inner loop is over the set of rows. A word mask stores the cumulative results of AND operations over the rows of a block of documents. In many cases, this word mask will become zero in the inner loop before all of the rows have been examined. Since additional intersections cannot change the result, it is possible to break out of the inner loop at this point.

// excerpt of query logic

for (b = 0; b < bitslicedsig->num_blocks; b++)

{

word_mask = -1;

for (r = 0; r < bitslicedsig->m; r++)

{

isSet = querysig[r >> WORD_POW] & (1ULL << mod_pow_2(r, WORD_SIZE));

if (isSet)

{

word_mask &= bitslicedsig->bit_matrix[r][b];

}

if (word_mask == 0)

{

// early termination of loop if no documents match

continue;

}

}

...

4 APPENDIX

4.1 Note on Code Design

Through completing this project, I wanted to gain experience designing and using bit-wise operations, structs, function pointers, file pointers, enums, linked lists, Makefiles, and other programming concepts I learned about in class. Here are some interesting design decisions that went into writing this code:

4.1.1 Bit-wise functions that take advantage of powers of 2

Division is a very slow operation. I can avoid division in many cases by taking advantage of the fact that in base 2, dividing by 2 is equivalent to a right bit shifting.

This piece of knowledge is behind these two more efficient lower-level helper functions I use in my program:

/**

* Returns a mod b

*

* b must be a power of 2

*/

u_int32_t mod_pow_2(u_int32_t a, u_int32_t b)

{

// if b is 2^n

// a mod b = last n digits of a

return a & (b - 1);

}

/** Returns power of 2 larger than n

*

* Operates in log(log(n)) bit shifts

*/

u_int32_t get_next_pow_2(u_int32_t n)

{

n--;

// Divide by 2^k for consecutive doublings of k up to 32, and then OR the results.

n |= n >> 1;

n |= n >> 2;

n |= n >> 4;

n |= n >> 8;

n |= n >> 16;

n++;

// The result is a number of 1 bits equal to the number of bits in the original number, plus 1.

// That's the next highest power of 2.

return n;

}

4.1.2 Function pointers for cleaner, reusable code

I can use function wrappers with function pointers in order to reuse code and make cleaner files. In bloom/test/test_bloom.c I define a wrapper function to parse string inputs into tokens in a consistent manner for insertion and querying.

void process_stream(test_results_t *test_res,

bloom_t *filter,

void (*operate)(test_results_t *, bloom_t *, char *),

FILE *stream

)

{

...

while (fgets(buffer, bufferLength, stream))

{

rest = buffer;

while ((token = strtok_r(rest, " !\"#$%%&()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\\]^_`{|}~", &rest)))

{

if (token[strlen(token) - 1] == '\n')

token[strlen(token) - 1] = '\0';

operate(test_res, filter, token);

}

}

}

// example of defined function I can use as an input

void operate_test_add_with_warning(test_results_t *test_res, bloom_t *filter, char *token);

This allows me to write add and lookup tests like this:

/* test add */

process_stream(&test_res, filter, operate_test_add_with_warning, options->fadd_to_bloom);

/* test lookup */

process_stream(&test_res, filter, operate_test_lookup_real_positives, options->fadd_to_bloom);

process_stream(&test_res, filter, operate_test_lookup_real_negatives, options->fcheck_in_bloom);

4.1.3 Flexible input using FILE pointers

I want my play programs to either read input from stdin, or read from a file, like the grep program does. I accomplish this by allowing my bit-sliced signature files to take a FILE pointer.

queryres_t *bitslicedsig_query(bitslicedsig_t *bitslicedsig, FILE *fquery);

This gives the play programs the flexibility of supplying either an opened file or stdin as according to the user defined flags.

For example:

## valid interaction

echo "hi my name is Gati" | ./bf_play -f bf_spellcheck.dat -v

## also valid interaction

./bf_play -f bf_spellcheck.dat -i README.md

4.1.4 Flexible output by Using Linked Lists for indeterminately sized result arrays

The bit-sliced document signature can output a variable number of matching documents. Storing these documents efficiently is an interesting problem. My first solution involved just printing the matching document IDs out directly from inside the bitslicedsig_query function. However, this is not a good practice because it limits the format options of the displayed output. A better method would be to store the matching outputs and return a pointer to the structure. For this, I had some different options:

On one hand, I could store the output document IDs in an array that is the size of the maximum number of documents. However, I know that the majority of documents are not going to be matches and allotting memory for a huge array, especially if there are many documents, is not ideal.

My alternative solution involved using a linked list. I implement the linked list in bitslicedsig/src/queryres.c. A linked list is a good choice for situations where the number of items is unknown and items are more likely to be accessed sequentially than via random access.

queryres_t *qr = bitslicedsig_query(bss, options->fread_input_from);

printf("\n%d Documents matching query: \n", qr->len);

res_t *ptr = qr->head;

while (ptr != NULL)

{

// here, the play program can decide the display format.

printf(options->output_format_string, ptr->data);

ptr = ptr->next;

}

By calling the program with:

echo "outside" | ./bss_play -f bss_xkcd.dat -s "https://xkcd.com/%d"

I can get a displayed result formatted like:

4 Documents matching query:

https://xkcd.com/30

https://xkcd.com/24

https://xkcd.com/16

https://xkcd.com/14

Where the document IDs are tied to a clickable url.

4.1.5 Enums and binary flags for display modes

For the bloom filter player bloom/demo/bf_play_main.c I use enums to designate the various output modes.

./bf_play -h

>> bf_play [-v] [-f file_load_bloom_from] [-i file_read_input_from]

[-s mode_display_selected] [-x mode_select_in] [-h]

Default: load Bloom filter from `bf_saved.txt`,

read input from stdin, m = 60, k = 3,

-s OFF (print all text),

-x OFF (color out-of-set terms red)

I use an enum and binary flags to designate the options:

## pseudocode

00 = ALL, OUT

01 = ALL, IN

10 = SELECTED, OUT

11 = SELECTED, IN

Examples of different combinations of output formats:

./bf_play -f bf_spellcheck.dat -i README.md -x

Output of demo spellcheck README option -x

./bf_play -f bf_spellcheck.dat -i README.md -s

Output of demo spellcheck README option -s

./bf_play -f bf_spellcheck.dat -i README.md -sx

Output of demo spellcheck README option -sx

4.1.6 Modular Design

I also wanted practice designing and writing clean, modular code. I accomplish this by making the decision to split the code for the actual data structure into a src folder (see bloom/src and bitslicedsig/src).

By encapsulating the code for the data structures, I was able to define a concrete API for the data structure and test that all the exposed functions of the API worked properly (see bloom/test and bitslicedsig/test).

After writing the test for the full end-to-end use-case, writing the demo programs was very easy; I just had to make sure the user interface was properly defined for each program and then call the appropriate data structure functions. Writing code in this way meant that my code base was reliable, predictable, and well organized. For example, my demos use an editor program and a player program. These each encapsulate a core functionality of interacting with the data structure (add and query, respectively).

The editor program (see bloom/demo/bf_editor_main.h and bitslicedsig/demo/bss_editor_main.h) creates a new data structure, or loads and edits an already saved data structure, and then saves the final results. This file thus uses create / load, add, and save functions of the corresponding data structure.

The play program (see bloom/demo/bf_play_main.h and bitslicedsig/demo/bss_play_main.h) loads the data structure from a file, and then processes queries from stdin or a file and displays the results in some pretty, user-customizable manner.

4.2 Note on Controlling False Positives

You can control the number of false positives (reduce collision) by increasing number of signature bits (m) and increasing number of hash functions (k).

The value of m configures how many bits will be allocated for the bit array. Ideally, when all the items are added, the bit array should be approximately half full. Worst case is if the bit array is completely full (all 1s), as it will say that every query may be in the filter (false positives). For performance reasons, the bit array rounds m to the nearest largest power of 2.

The value of k configures how many hash functions will be used in the Bloom filter hashing scheme. A higher number of hash functions means that there is a higher signal to noise ratio, where signal is the probability that a term is a member of a set given that all the term’s probes are present in the Bloom filter, and noise is the probability of a false positive. Rarer terms have a higher likelihood of being a false positive, so increasing k improves the signal to noise ratio and allows for better retrieval of rate terms. However, a larger k leads to more hash operations, and therefore slower insertion and lookup time. The seeds of the hash function are generated with a random number generator in order to be independent and uniformly distributed.

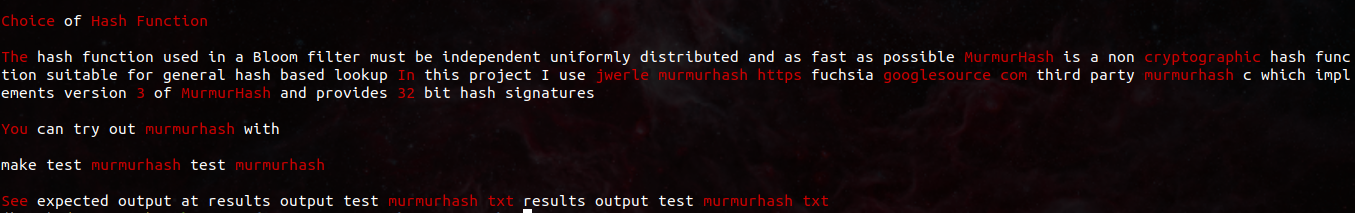

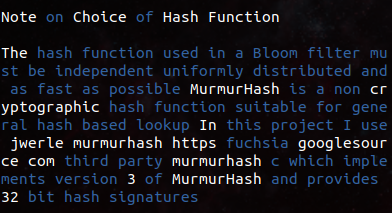

4.3 Note on Choice of Hash Function

The hash function used in a Bloom filter must be independent, uniformly distributed, and as fast as possible. MurmurHash is a non-cryptographic hash function suitable for general hash-based lookup. In this project, I use jwerle/murmurhash which implements version 3 of MurmurHash and provides 32-bit hash signatures.

You can try out murmurhash with

make test_murmurhash && ./test_murmurhash

See expected output at results/output_test_murmurhash.txt.

5 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Currently, the Bloom filter and bit-sliced signatures perform exact keyword search. However, there are situations where a fuzzier keyword search is desirable (lower precision but higher recall). Ways to make a fuzzy keyword search include:

- lowercasing terms before adding and and querying

- removing ’s’ from terms so that extra space is not used to store singulars and plurals of the same word

- using a stemmer (like Snowball Stemmer) to break terms down into their root word. In this senario, words with the same root, like “running”, “runs”, and “ran” would all be condensed to “run” before add and query.

Frequently a fuzzy keyword search is not desirable because it introduces extra noise. Depending on the preprocessing, which can introduce extra time and resource costs. For this reason, Bing’s BitFunnel algorithm does not use stemming.