A survey of data structures used in large-scale information systems. Covers (i) how the inverted index data structure allows for constant time querying (ii) the need, problems, and clever design details of methods to compress big numbers (focusing on Elias-Fano and Partitioned Elias-Fano), and (iii) BitFunnel, an unusual probabilistic data structure used by the Bing search engine to bypass the curse of inverted index global updates.

5-minute video summary:

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION

- 3 ELIAS-FANO COMPRESSION

- 4 PARTITIONED ELIAS-FANO COMPRESSION

- 5 BITFUNNEL: ALTERNATIVE TO INVERTED INDEXES

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

1 INTRODUCTION

Information retrieval is not a new problem: humans have been compiling, storing, and organizing books and scrolls and papyrus for more than 5,000 years. What has changed, however, is the scale of the task. For most of human history, methods of information retrieval was a subject of interest restricted to librarians, bookkeepers, and information experts. However, in the modern era, with the introduction of smartphones, cheaply available sensors, and more than 4 billion people using and contributing to the Internet every day, the rate of information generation and storage has escalated. Research into fast and compact ways of finding information becomes more relevant every day. Figure 1 shows various companies and products that rely on efficient information retrieval.

Figure 1: Information retrieval is a ubiquitous task.

2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION

An information retrieval (IR) system attempts to solve The Matching Problem, where given a query, it wants to retrieve a set of documents that are relevant or useful to the user. Solving this problem requires a system to manage document indexing, retrieval, and ranking. The diagram in Figure 2 shows how documents and user queries get processed by an IR system.

![Figure 2: High level software architecture of an IR system: Indexing, Retrieval, and Ranking [2].](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/overview.png)

Figure 2: High level software architecture of an IR system: Indexing, Retrieval, and Ranking [2].

An example of an IR system is a search engine, like Google or Bing. Search engines use a complex blend of technologies to process user queries, decipher intent, and rank documents by relevance. The inner workings of the ranking stage of IR systems are configured by machine learning [6].

If there were unlimited resources, each query could be processed by asking the ranking oracle to look at every single document in the corpus and return the top ranked documents. However, this is not feasible in practice; to save time, space, and computation costs, the data retrieval stages of all large-scale IR systems rely on a data structure called an inverted index.

2.1 Inverted Indexes For Fast (Constant Time) Lookup

The theory behind an inverted index says, with some preprocessing upfront, finding which set of documents contains a single term can be done in constant time. An inverted index can be thought of as a hashmap, where the keys are terms and the values are a list of document IDs, or pointers, stored in monotonically increasing order (see Figure 3 for an example). The list of document IDs is also called a postings list. To process a query, the algorithm scans the posting list of each query term concurrently, keeping them aligned by document ID.

![Figure 3: It is an “inverted” index because instead of mapping what words are in a document, it is an inverted map of what documents are associated with each word [14].](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/inverted_index.png)

Figure 3: It is an “inverted” index because instead of mapping what words are in a document, it is an inverted map of what documents are associated with each word [14].

2.2 Big Document IDs Use a Lot of Space

Googling the word “the” returns “About 25,270,000,000 results”.

Figure 3: Google results for the word ’the'

Assuming each result document ID is stored as a unique 4-byte unsigned int, the document IDs alone take up 101.08 Gigabytes of space. It gets worse. The number 25,270,000,000 is actually greater than the upper range of numbers that can be expressed by a 4-byte unsigned int ($2^{32}$) so to ensure all the results have unique document IDs, these numbers need to be stored in a 8-byte representation, resulting in a mighty 202.16 GB minimum just to store the document IDs for part of the postings list for the word “the”. When dealing with a gigantic corpus, like the billions of documents on the Internet, document IDs can be very large, and storing big numbers consumes significant amounts of memory.

Google, Bing, and other big data information retrieval systems care deeply about reducing memory consumption for storing large numbers. One solution to this dilemma is using inverted index compression codes. These are completely invertible transformations that map the large integers of the document IDs onto smaller integers that require less bits. As an added bonus, by using compression codings, storing and accessing the inverted index from RAM becomes feasible. This can lead to faster indexing and query response times compared to storing and retrieving from slower hard disk or SSD.

2.3 An Overview of Compression Codes: Balancing Space Savings and Time Cost

While using a compression code saves memory, it also increases retrieval and indexing time, as there are time and computation costs for compression and decompression. The choice of compression code balances the tradeoff between saving memory and increasing query time.

For example, the smallest compressed inverted index is Binary Interpolative Coding (BIC). It is ~3x smaller and ~4.5x slower than the fastest inverted index, Variable-Byte (VByte) [10]. A IR system wants codes that are small when compressed and fast to decode. Production IR systems tend to use PFOR or PEF because they have good memory compression to time cost ratios. The charts in Figure 4 show the time and space tradeoff of common compression algorithms.

![Figure 4: Compression Codes: the trade-off between spacing savings and decompression time costs [10].](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/compression_code_performance.png)

Figure 4: Compression Codes: the trade-off between spacing savings and decompression time costs [10].

BIC manages to reach its astounding compression ratio by recursively splitting monotone integer sequences in half so each split’s range is reduced, thus reducing the number of bits to encode it. Several experiments show BIC is the smallest way to encode highly clustered and sequential clusters of integers. However, decoding the recursive code is very slow.

VByte encoding uses byte-aligned representations, making it faster than bit-aligned representations. It splits each positive integer x into groups of 7 bits and makes the eighth bit a continuation bit, which is equal to 1 only for the last byte of the sequence.

VByte is part of the delta coding / gap compression family of compression codes. This family includes: Elias Gamma code, Elias Delta code, Elias Omega code, Golomb / Rice code, and Elias-Fano code. They compress by calculating and storing the delta values (gaps) between consecutively ordered document ID. Since the deltas are always smaller than the document IDs themselves, encoding takes fewer bits and achieves compression. The search engine Lucene (backbone of elasticsearch and Solr) used to use VByte codes [13]. Lucene currently uses the Elias-Fano code.

Frame-of-reference (FOR) codes balance a good tradeoff between compression ratio and speed by simultaneously encoding blocks of integers. For each block, FOR encodes the range enclosing the values in the block. This technique is also called binary packing and is also used by the Simple family of codes. In order to keep the ranges small, a variant called PForDelta uses a technique called patching to encode outliers. The Google search engine uses GroupVarint [5], a variant of PForDelta.

3 ELIAS-FANO COMPRESSION

This section discusses implementation details from the 2013 paper “Quasi-Succinct Indices” [13], by Sebastiano Vigna, researcher on MG4J. Please see paper for full proofs and details.

3.1 Introducing Quasi-Succinct Elias-Fano: Fast, Small and Better than Sequential Decoding

Many classic compression codes only allow sequential decoding. To process a query, the lists involved need to be entirely decompressed, even if just one of the values was required. Inverted indexes compressed with the classic compression codes have fast sequential access, but slow performance on random access and next greater than or equal to (NEXTGTE) queries used by IR data retrieval tasks.

In contrast, the Elias-Fano code delivers slightly slower sequential access, but achieves fast performance on random and NEXTGTE queries. In addition to the time efficiency, Elias-Fano is quasi-succinct, meaning it is less than half a bit away from the best theoretical compression scheme in terms of space.

Succinct data structures use $n + o(n)$ bits of storage space (the original bit array and an o(n) auxiliary structure to support two basic operational building blocks [12]:

- $rank_{q}(x)$: return the number of elements equal to $q$ up to position $x$ in the array

- $select_{q}(x)$: returns the position of the $x$-th occurrence of $q$

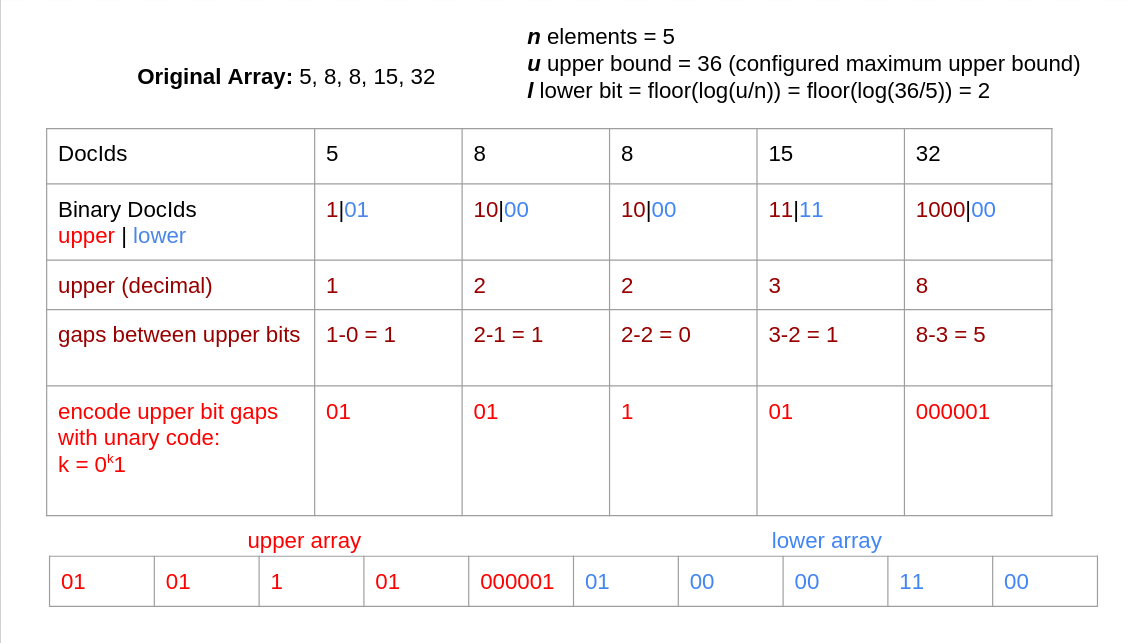

Elias-Fano is quasi-succinct because it uses at most $2 + ceil(log(u/n))$ bits per element, where n is the number of elements and u is an upper bound on the range. The lower $l = max(0, floor(log(u/n)))$ bits of each element are stored explicitly and contiguously, and the upper bits are stored as a sequence of unary coded gaps (see Figure 5 for an example).

Figure 5: Elias-Fano compression, represent each document ID in a gap-encoded compact representation.

Since each unary code uses one stop bit and there are n elements, the higher bit array can at most contain n ones and 2n zeros. This representation makes searching (see Figure 6 for an example) and skipping fast and easy.

Figure 6: Elias-Fano decompression, use rank and select to perform non-sequential decompression.

3.2 Speed-Up Elias-Fano with Quantum Skipping

For quick (average constant-time) reading of a sequence of unary codes, the $rank_{q}(x)$ and $select_{q}(x)$ operations can use a short-cuts: instead of counting all the ones and zeros to the left of an element, the upper bit array can incorporate fixed $q$-distance apart pointers that store the position of each $q$-th zero or $q$-th one in a table. Using random access, one can go to the $q$ position in constant time and search from there. This allows for extreme locality: only one memory access per skip!

This has been a brief overview of the math behind Elias-Fano. In practice, Elias-Fano in performance critical information systems takes advantage of many interesting implementation details like caching and long-word addressing. There are extensions to Elias-Fano for recording term counts and term positions in documents that build upon the concepts mentioned above. Details are in the paper.

3.3 Review of Elias-Fano

Elias-Fano is widely adopted as a dominant compression scheme in IR systems. Today Elias-Fano is the compression scheme for Lucene [1] (the backbone of elasticsearch and Solr), MG4J [11] (search engine used as an IR research test-bed), and Facebook’s Graph Search [4].

Compared to other compression codes, Elias-Fano has a fast decoding speed and fast locality of access, while still saving a decent amount of memory through compression. Elias-Fano performs very well on boolean-and queries that require heavy skipping to find phrases. It is also efficient when coupled with optimally lazy proximity algorithms [3], or when the values accessed are scattered in the list; this is common in conjunctive queries when the number of results is significantly smaller than the sequences being intersected.

Elias-Fano performs badly on sequential, enumeration oriented tasks that do not rely heavily on skipping. It also does not have any optimizations for handling common phrases (e.g. “home page”)

4 PARTITIONED ELIAS-FANO COMPRESSION

This section discusses implementation details from the 2014 paper “Partitioned Elias-Fano Indexes” [9], by Giuseppe Ottaviano and Rossano Venturini. Please see paper for full proofs and details.

4.1 For Better Compression, Take Advantage of Naturally Occuring Document ID Clusters

Elias-Fano assumes document IDs in a postings list are randomly distributed, and its encoding uses the minimum quasi-succinct space needed to represent a sequence of random numbers. However, in real life, document IDs are not randomly distributed, and taking advantage of natural document ID clusters allows for even better compression.

“Crawler” is a generic term for any program (such as a robot or spider) that is used to automatically discover and scan websites by following links from one webpage to another. Using a crawler to find new documents to index means consecutively indexed pages are generally from the same site or on the same topic. These pages frequently have similar vocabularies, which creates clusters of consecutive document pointers in the postings list. These consecutive document IDs can be compressed more than randomly spaced numbers (see Figure 7).

![Figure 7: Elias-Fano fails to exploit the clustering formed by crawlers consecutively encountering documents using the same vocabulary [6]. 7a.) natural cluster of document IDs 7b.) comparison of random sequence versus highly compressible consecutive sequence](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/partitioned_elias_fano_improvements.png)

Figure 7: Elias-Fano fails to exploit the clustering formed by crawlers consecutively encountering documents using the same vocabulary [6]. 7a.) natural cluster of document IDs 7b.) comparison of random sequence versus highly compressible consecutive sequence

Partitioned Elias-Fano (PEF) compression improves upon the Elias-Fano compression by building a two-layer data structure. It partitions the sequence into chunks that take advantage of clusters, replaces chunks with pointers that mark the beginning of each chunk (see Figure 8), and then compresses the sequence of pointers with Elias-Fano to support fast random access and search operations.

![Figure 8: PEF chunks sequences and stores pointers [8]](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/partitioned_elias_fano.png)

Figure 8: PEF chunks sequences and stores pointers [8]

4.2 Speed-Up PEF Partitioning with Dynamic Programming on a Sparsified DAG

PEF needs to decide where to draw the partition lines in order to make the most compressible document ID chunks. Unfortunately, exhaustive search is exponential. Luckily, drawing partition lines is a generalization of the weighted interval scheduling problem, so PEF can use dynamic programming to perform the search in quadratic time.

The problem can be represented as a search for the minimal cost path on a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where each node is a document ID, and each edge weight is the cost of the chunk defined by the edge endpoints. Each edge cost can quickly be computed in O(1). However, evaluating all the edges is quadratic with the number of document IDs. More optimization is required for a scalable system. To further narrow the search space, PEF uses two general DAG sparsification techniques to reduce the number of evaluated edges from quadratic to linear (See Figure 9).

Technique 1: Since the partition does not have to be optimal, only workably “good enough”, instead of evaluating every combination of edges, PEF can select and evaluate on a handful of promising edges. PEF selects promising edges by binning edge costs into cost classes, and for each node and each cost class, greedily keeping one best edge.

Technique 2: Cost differences between arbitrarily split chunks are negligible if the chunks are big enough. Thus, the search space can be trimmed by removing edges via a loss thresholding function.

![Figure 9: PEF turns quadratic edge search (grey) into a linear edge search (red) [8]](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/sparsification.png)

Figure 9: PEF turns quadratic edge search (grey) into a linear edge search (red) [8]

4.3 Review of Partitioned Elias-Fano

By using the two-level partitioned compression, PEF indexes offer up to double [8] the compression of plain Elias-Fano while preserving its query time efficiency. Compared to other state-of-the-art compressed codes (paper compared PEF to PForDelta variant OptPFD), PEF exhibits the best compression to query time trade off. PEF is very good for search engines that use crawlers to consecutively discover related pages as it can compress clusters of documents that are similar due to their shared vocabulary.

5 BITFUNNEL: ALTERNATIVE TO INVERTED INDEXES

This section discusses details from the 2017 paper “BitFunnel: Revisiting Signatures for Search” [7], by Bob Goodwin, Micheal Hopcroft, Dan Luu, et. al. Please see paper for full proofs and details.

5.1 Inverted Indexes, the Curse of Global Updates, and the BitFunnel Alternative

While inverted indexes are the backbone of all large-scale IR systems, they have an serious drawback: adding a new document requires a global update to all posting lists for all the terms contained in the new document. This is a costly operation, so generally, inverted indexes are either static (only indexed once), or updated in batches using MapReduce.

However, search engines cannot always wait for batch updates in order to serve new documents. For example, when news happens and people search for the news, they want to see it right away. Researchers at Microsoft found a compact and fast solution that used a technology that was once considered unusable. The BitFunnel algorithm addresses fundamental limitations in bit-sliced block signatures and is used in the Bing search engine today.

5.2 Bloom Filters: Fast, Compact, and Sometimes Wrong

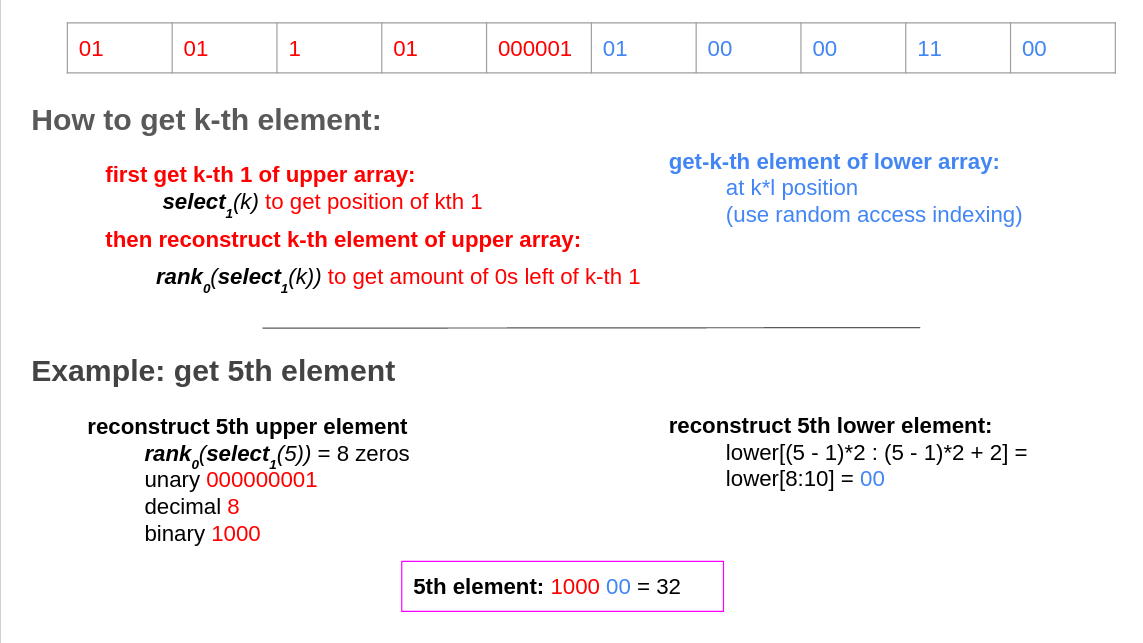

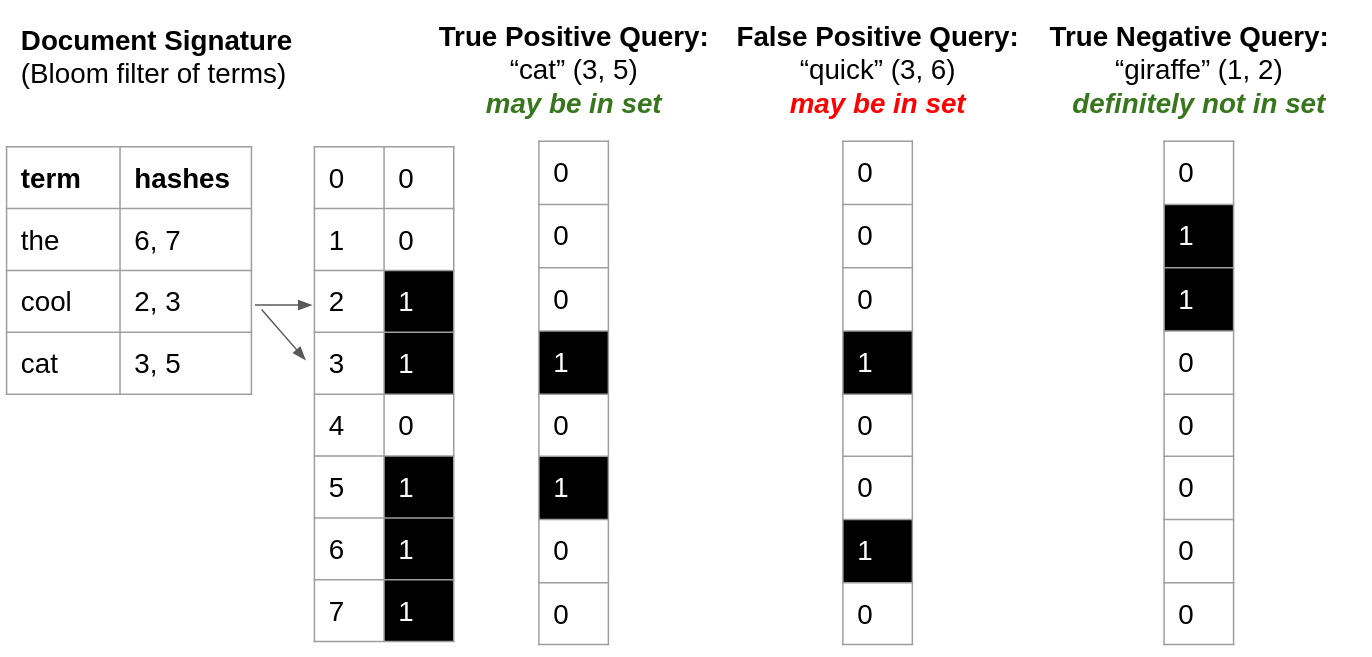

BitFunnel uses minimal space while enabling rapid querying of the fresh collection of documents that have not been batch updated into the main inverted index. It does this by representing each document in the corpus by a signature. This signature is a Bloom filter representing the set of terms in the document (see Figure 9). A Bloom filter is a probabilistic data structure, meaning it does not store the terms directly, it stores indicators (a.k.a. hashes, probes) of each term’s presence.

Figure 10: Bloom Filter can return false positives but cannot return false negatives

If all the signatures have the same length and share a common hashing scheme, each document can be represented by a bit-sliced signature. In this approach, document signatures are stored in a big table, like a nested array of machine words (32-bit integers). Each row corresponds to one hash key. In the row, each of the 32 bits in an element correspond to 32 documents, and the bit is on or off depending on whether the document has the hash key (see Figure 10). Since each document has its own column, adding a new document only requires a local update to the specified column.

![Figure 11: BitFunnel Table Layout with bit-sliced signatures, in which each column is a document signature. Q is the signature of the query [Annotated By Gati Aher] [7]](/projects/survey-of-data-structures-for-large-scale-information-retrieval/img/bitfunnel.png)

Figure 11: BitFunnel Table Layout with bit-sliced signatures, in which each column is a document signature. Q is the signature of the query [Annotated By Gati Aher] [7]

Given a query, BitFunnel builds a query signature by hashing each term in the query with the same bag of hash functions, and then checks if any of the document signatures have all of the query hashes. If all of the query hashes are not present in the document signature, there is no possibility of the document containing all of the terms in the query. However, since sets of terms can have the same hashes, there is a possibility of falsely saying all the query terms are in the document.

5.3 Being Wrong Less Often: Managing the False Positive Rate

BitFunnel is okay with a small possibility of false positives as long as its impact on the end-to-end system is low. BitFunnel is designed to filter out documents that would score low in the ranking system, while never rejecting documents that score high. In the later IR ranking phase, machine learning algorithms can reject obvious false positives. BitFunnel uses two optimizations to reduce memory consumption and false positive rates.

Optimization 1: If documents have many terms, increasing $m$, the length of the signature bit vector, can keep the bit vector from filling up. If a bit vector fills up, say all of its bits are set to 1, then it will say every query exists in the document set. Ideally, a bit vector should have about half of its bits set. BitFunnel saves space by sharding the corpus into bins by document length. This allows BitFunnel to use smaller $m$ bit-sliced signatures to store shorter documents and larger $m$ bit-sliced signatures to store larger documents. While normally sharding a document is not advisable because of overhead costs, when an index is many times larger than the memory of a single machine it must be sharded anyway. By sharding intelligently by document length instead of some arbitrary factor, BitFunnel saves memory.

Optimization 2: Identification of terms requires a good signal to noise ratio. Signal, $s$, is the probability that a term is actually a member of the document. Noise, $\alpha$, is the probability that a term’s $k$ probes are set to 1 in the document signature, given that the term is not in the document. Assuming the Bloom filter is configured to have an average bit density $d$, the density is the fraction of bits expected to be set. Therefore, one can use simple probability math to solve for the minimum value of $k$ to ensure a certain signal-to-noise ratio $\phi$ (see paper). The main takeaway is rare terms have a lower signal value and thus require more $k$ hashes to ensure a given signal-to-noise level. BitFunnel saves space and prevents the bit vector from filling up by using a Weighted Bloom Filter to adjust the number of hash functions on a term-by-term basis within the same Bloom Filters.

5.4 Review of BitFunnel

BitFunnel is a fast and compact probabilistic data structure that allows a new document to be added in constant time with a single local update. At lower document numbers BitFunnel outperforms Elias-Fano inverted indexes in terms of memory usage, document add times, and data retrieval times. As the collection size grows the performance gap gets thinner, and at higher numbers, BitFunnel performs worse, as BitFunnel query execution is linear with the collection size, while inverted indexes have empirical performance closer to the number of returned results. Thus, BitFunnel performs its duty as a compact and fast probabilistic filter for querying a collection that has not entered the main inverted index, but it should not replace the inverted index in terms of being the main indexing structure.

CONCLUSION

All large-scale information retrieval systems use inverted indexes for efficiently performing data retrieval based on keyword search. Over the years, as data storage needs grew, several inverted index compression codes were suggested for reducing the memory used to store large document pointer numbers in postings lists. A commonly used compression code with a good memory compression to query retrieval speed ratio is Elias-Fano, which uses a quasi-succinct mathematical data structure that allows for constant time querying on average and a memory usage close to the theoretical optimal bound. Partitioned Elias-Fano improves upon Elias-Fano by taking advantage of the high occurrence of sequential document pointers in a postings list. It uses a dynamic programming technique to determine the best partitioning scheme for compressing sequential document IDs and then forms a two-level compressed data structure.

Adding a new document to an inverted index requires a costly global operation to update the posting list for each term in the document. To save time on this operation, invented indexes generally use batch updates. In order to support user queries on documents that are waiting on the batch update, e.g. people searching for real-time news, Bing uses a probabilistic data structure called BitFunnel that can ingest new documents with a quick local update while also supporting rapid keyword search.

BONUS: Partially Implementing BitFunnel!

In order to understand the BitFunnel data structure better, I implemented a Bloom filter and a bit-sliced document signature in C. I also wrote tests to make sure my implementations worked as expected, and fun demos to show how these data structures can be used. More details and a writeup are available at BloomForSearchFromScratch.

As a fun information retrieval demo, I decided to use my bit-sliced document signature to retrieve xkcd comics that match keywords. This is a fun tool to explore new xkcd comics for a topic.

In this demo, I add 40 documents (allocating two blocks of 64 bits), use signatures of length 512, and 3 hashes on each term. Each document comprises of the title, alt-text, and transcript of a given xkcd comic. This information is scraped from https://www.explainxkcd.com/ using a Python script with beautifulsoup.

As a demo query, I search for the term “outside”. This word actually appears in two documents: 30 and 14.

Here is an excerpt of the final results:

---------------------------------

Bit-Sliced Block Signature

m = 512, k = 3, num_blocks = 2

39/64 docs added

hash_seeds = 28 10 6

array =

197188 0

16908928 8

1694507008 0

17306112 0

17104896 0

-946130846 49

1092625410 0

1611989056 0

-105968822 187

165224480 8

... [output truncated]

colsums = 0 103 69 23 69 162 175 82 83 160 95 68 116 206 85 89

324 167 155 219 263 122 88 212 428 56 92 98 88 207 159 97

220 71 65 114 80 122 97 89 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

percent filled = 0=0.00% 1=0.20% 2=0.13% 3=0.04% 4=0.13% 5=0.32% 6=0.34% 7=0.16%

8=0.16% 9=0.31% 10=0.19% 11=0.13% 12=0.23% 13=0.40% 14=0.17% 15=0.17%

16=0.63% 17=0.33% 18=0.30% 19=0.43% 20=0.51% 21=0.24% 22=0.17% 23=0.41%

24=0.84% 25=0.11% 26=0.18% 27=0.19% 28=0.17% 29=0.40% 30=0.31% 31=0.19%

32=0.43% 33=0.14% 34=0.13% 35=0.22% 36=0.16% 37=0.24% 38=0.19% 39=0.17%

40=0.00% 41=0.00% 42=0.00% 43=0.00% 44=0.00% 45=0.00% 46=0.00% 47=0.00%

48=0.00% 49=0.00% 50=0.00% 51=0.00% 52=0.00% 53=0.00% 54=0.00% 55=0.00%

56=0.00% 57=0.00% 58=0.00% 59=0.00% 60=0.00% 61=0.00% 62=0.00% 63=0.00%

---------------------------------

Sucessfully saved bit-sliced signature to bss_xkcd.dat!

echo "outside" | ./bss_play -f bss_xkcd.dat -s "https://xkcd.com/%d"

4 Documents matching query:

https://xkcd.com/30

https://xkcd.com/24

https://xkcd.com/16

https://xkcd.com/14

My probabilistic data structure returns 4 matches: 30, 24, 16, 14. As expected there are the two true positives and no false negatives. However, documents 16 and 24 are false positives. Upon taking a closer look, the document signatures for documents 16 and 24 are 63% and 84% full respectively. That means, each bit has a higher than random chance possibility of being flipped, so the probability of the query hash being falsely present in the signature is pretty high.

To reduce the rate of false positives, I can increase the length of the bit signature so that it is less full. If I was using bit-sliced signatures in a production system, there are some interesting optimizations that reduce query speed, memory usage, and false positive rate (e.g. intelligent corpus sharding, weighted Bloom filters).

REFERENCES

- “Class EliasFanoEncoder.” Lucene Java Docs, 4.8.0 , lucene.apache.org/core/4_8_0/core/org/apache/lucene/util/packed/EliasFanoEncoder.html.

- Baeza-Yates, Ricardo. “Chapter 1, Introduction.” Modern Information Retrieval, edited by Berthier Ribeiro-Neto, 2nd ed., Addison Wesley Longman Publishing Co. Inc., 2011.

- Boldi, Paolo, and Sebastiano Vigna. “Efficient Optimally Lazy Algorithms for Minimal-Interval Semantics.” Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 648, 8 Oct. 2016, pp. 8–25., doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2016.07.036.

- Curtiss, Michael, et al. “Unicorn: A System for Searching the Social Graph.” Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, vol. 6, no. 11, 2013, pp. 1150–1161., doi:10.14778/2536222.2536239.

- Dean, Jeffrey. “Challenges in Building Large-Scale Information Retrieval Systems.” Proceedings of the Second ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining - WSDM ‘09, 2009, doi:10.1145/1498759.1498761.

- Gog, Simon, and Rossano Venturini. “Succinct Data Structures in Information Retrieval.” Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2016, doi:10.1145/2911451.2914802.

- Goodwin, Bob, et al. “BitFunnel: Revisiting Signatures for Search.” Proceedings of the 40th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2017, doi:10.1145/3077136.3080789.

- Ottaviano, Giuseppe, and Antics. BitFunnel: Revisiting Signatures for Search [Pdf] , 4 Sept. 2017. https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=15169524

- Ottaviano, Giuseppe, and Rossano Venturini. “Partitioned Elias-Fano Indexes.” Proceedings of the 37th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, 2014, doi:10.1145/2600428.2609615.

- Pibiri, Giulio Ermanno. “Space- and Time-Efficient Data Structures for Massive Datasets.” University of Pisa, 2019, pages.di.unipi.it/pibiri/slides/final_PhD_presentation2.pdf.

- Vigna, Sebastiano, and Paolo Boldi. “Class QuasiSuccinctIndexWriter.” MG4J: High-Performance Text Indexing for Java™, 5.4.4., mg4j.di.unimi.it/docs-big/it/unimi/di/big/mg4j/index/QuasiSuccinctIndexWriter.html.

- Vigna, Sebastiano. “Broadword Implementation of Rank/Select Queries.” Experimental Algorithms, 29 Mar. 2020, pp. 154–168., doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68552-4_12.

- Vigna, Sebastiano. “Quasi-Succinct Indices.” Proceedings of the Sixth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining - WSDM ‘13, 8 Feb. 2013, doi:10.1145/2433396.2433409.

- Zobel, Justin, and Alistair Moffat. “Inverted Files for Text Search Engines.” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 38, no. 2, 2006, p. 6., doi:10.1145/1132956.1132959.